|

corporate history

The Grumman Corporation of

Bethpage, New York, has

been one of the handful of

military aircraft builders

since the 1940s. During

World War II it

manufactured a series of

U.S. Navy fighter planes

that were highly

dependable and resilient.

Grumman was the Navy's

prime aircraft

manufacturer in the early

1940s and most of its

business came from the

Navy. But after the war,

as other companies began

vying for navy contracts,

Grumman decided to

diversify and build some

non-military planes. It

also entered the new field

of space flight. Still,

from the late 1940s to the

company's demise in 1994,

Grumman maintained a

strong relationship with

the Navy and built several

key aircraft for the

seafaring service.

As World War II was

ending, the aviation

industry began developing

the jet engine. A new era

of flight was dawning, and

Grumman engineers worked

on perfecting the new

technology. By 1949, they

had created the F9F

Panther, the company's

first combat jet and the

Navy's primary fighter

plane of the Korean War.

It was a carrier-based

aircraft that used several

weapons systems and

handled a variety of

missions ranging from

protecting heavy bombers

to photoreconnaissance. It

also excelled at

individual strafing and

bombing runs. During the

war, F9Fs would fly more

than 78,000 combat

missions.

In the mid 1950s,

competition among various

aircraft companies for

military business became

intense. One corporation,

McDonnell, was

particularly interested in

securing a navy contract

for an all-purpose

fighter. McDonnell edged

Grumman out as the Navy's

top supplier of jet

fighters with its superior

Phantom. It would take

Grumman more than a decade

to design a plane that

would supplant the

Phantom.

Despite Grumman's loss to

McDonnell, the company

continued to build some

key naval aircraft,

especially surveillance

and detection planes. In

1953, Grumman introduced

the S2F Tracker, a

hunter/killer aircraft.

This twin-engine plane

excelled at electronic

tracking and antisubmarine

warfare; it would "hunt"

down its enemy using its

detection equipment and

then "kill" it with its

vast array of weapons. The

Tracker was the first U.S.

carrier-based

hunter/killer.

In February 1958, Grumman

produced its second major

naval surveillance plane.

The WF-2 Tracer was the

first carrier-based

airborne early-warning

aircraft. It could detect

enemy offensive weapons at

great distances and

coordinate friendly

aircraft for a

counter-attack. One of the

most remarkable aspects of

the Tracer was the large

radar dish that rested on

top of the plane's

fuselage. The radar looked

like a huge mushroom and

was almost two-thirds the

size of the actual plane.

The Tracer became one of

the premier intelligence

planes of the late 1950s

and remained that way

until Grumman improved it

and built the Hawkeye.

The E-2B Hawkeye, which

first came into service in

October 1960, has remained

one of the most important

US military planes to

date. With

state-of-the-art

surveillance equipment,

and the ability to refuel

in flight, the Hawkeye

was, and newer models

continue to be, one of the

most advanced surveillance

aircraft. In the mid

1970s, its ATDS (airborne

tactical data system)

could track as many as 200

enemy targets at once and

develop a logical counter

strike plan. In 1991, the

Hawkeye played a key role

in the Persian Gulf War

and in 2002, is poised to

make some vital

contributions to America's

war on terrorism.

When Grumman lost its hold

as the prime manufacturer

of the Navy's first strike

fighter, it decided to

diversify and build

products for the

commercial market. One of

its first successes was

the 1956 Ag-Cat, a

single-seat, crop-dusting

biplane. In 1958, Grumman

unveiled its Gulfstream, a

small corporate,

land-based transport plane

that held 19 passengers.

The Gulfstream was a huge

commercial success. In

fact, it did well enough

to warrant another model,

the Gulfstream II, a

twinjet that debuted in

October 1966. Grumman even

built canoes, a few

experimental hydrofoil

boats, a submarine, and

delivery trucks in the

1950s and 1960s.

Despite Grumman's move

into the commercial

market, it still kept

entering design

competitions for navy

combat planes. In the late

1950s, the strategy paid

off when the Navy selected

Grumman to build a new

all-weather, low-altitude

attack plane. Although not

the top-of-the-line

fighter that Grumman most

desired, the A6 Intruder

was still a key combat

plane. Able to hold a

pilot and bombardier, this

carrier-based, subsonic

attack aircraft entered

service in April 1960 and

became an important weapon

during the Vietnam War.

With an electronic

attack-navigation system,

the Intruder faired quite

well against the enemy. It

also carried approximately

nine tons of bombs and

missiles. By 1965, the

Navy was so pleased with

the A-6 that it asked

Grumman for a more

advanced model—the EA-6B

Prowler. Essentially a

more sophisticated version

of the Intruder, it

incorporated a more

advanced electronic

countermeasures system and

a crew of four. The

Prowler saw heavy service

during the Persian Gulf

War and will undoubtedly

be an important weapon in

the war on terrorism.

When Grumman was

diversifying in the late

1950s, a huge new

market—space flight—opened

up. Grumman entered any

space design competition

it could. In 1960, it won

the contract for the

Orbiting Astronomical

Observatories (OAO). These

observatories were the

first space telescopes,

the direct forerunners of

the Hubble Space

Telescope. They were

serious scientific

instruments that provided

scientists with new views

of the universe. Grumman

built four OAOs in all.

Grumman's experience with

the OAOs helped it win the

contract for the Apollo

Lunar Module (LM), the

spacecraft that the U.S.

astronauts used to land on

the Moon. The LM was the

world's first true

spacecraft because it

operated totally outside

the Earth's atmosphere.

Many contemporaries called

it the "bug" because of

its four insect-like

looking landing legs that

attached to a gold

Mylar-covered, cube-shaped

descent stage. This stage

held the engine that

allowed it to descend to

the lunar surface. On top

of the descent unit rested

the ascent stage with the

ship's control room and

the engine that lifted it

off the Moon. Perhaps the

most important LM was not

the first one that landed

on the moon during the

July 1969 Apollo 11

mission but rather the one

the Apollo 13 astronauts

used as a "lifeboat"

during their ill-fated

mission in April 1970. In

all, Grumman built 12 LMs,

six of which landed on the

Moon.

While Grumman was busy

manufacturing the LMs, the

company was also trying to

regain its position as the

Navy's top supplier of jet

fighters. Grumman

engineers began working on

a new fighter design

almost as soon as the

McDonnell Phantom

appeared. Their new

concept, a

variable-sweep-wing

fighter, first surfaced in

a design for the F-111B in

1964, but because the

F-111B never made it past

the prototype phase, due

to military inter-service

quarrelling, Grumman

engineers added the

variable-sweep-wing

concept to their new F-14

Tomcat. The Navy was

impressed with the plane

and agreed to make it

their front-line jet

fighter. In September

1972, the Tomcat began

replacing the Phantom on

U.S. aircraft carriers and

naval bases. Because it

could travel at Mach 2.5

at both ground and sea

level, and its extremely

flexible and superior

weapons system, the F-14

remained the Navy's best

all-around fighter for

well over 20 years.

Grumman began to run into

serious financial

difficulties in the 1980s.

Although it continued to

build Tomcats and Hawkeyes

well into that decade, the

end of the Cold War

seriously hurt the

military aviation market

and Grumman suffered

accordingly. Even though

the company had endured

massive layoffs after

World War II, with its

workforce falling from

approximately 25,500 to

3,300, it had still built

itself back up to around

37,000 workers by the mid

1960s. Nevertheless, by

1994, the company was

facing serious enough

financial problems that it

could no longer stand on

it own. Northrup, a

competing company,

purchased and subsumed

Grumman, forming the

Northrop Grumman

Corporation. For more than

60 years, Grumman had been

one of America's most

important military

aircraft builders and had

also built the spacecraft

that put humans on the

moon. But shortly after

the Cold War ended, a war

that had helped Grumman

thrive, the Long Island

company met its demise.

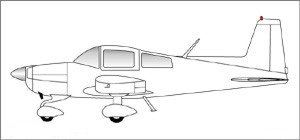

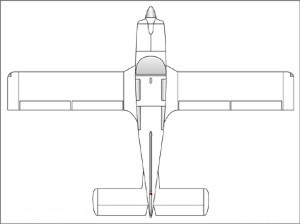

A Homebuilt in Certified

Clothing (The Yankee

AA1)

The Yankee AA1 was

originally designed by Jim

Bede (of the Bede 4, 5,

and 10 fame) as the Bede

1. It was to be an

everyman's aircraft: easy

to build, fun to fly, and

aerobatic with

folding-wing, take-home

capabilities. But the

"everyman's" status was

never achieved. Bede was

ousted and the company was

renamed and reorganized as

American Aviation.

American took over the

production and design,

trying to turn the

exciting little two- seat

aircraft into a civilized

"production" plane.

Modifications included a

108-hp engine (instead of

the original 65 hp),

non-aerobatic, and

stay-at-the-airport

dimensions. It also became

a

stay-on-the-airport-runway

airplane; the original

design might have been

better, but it was not to

be.

The Yankee is a

neat-looking aircraft,

made from a different

process. The fuselage is a

sandwich of aluminium

honeycomb material that is

bonded (glued) together

(another forerunner to the

composite craze?). The

fuel tanks are also the

wing spars. The aluminium

tube fuel tank/spars are

small - only 22 gal, which

should mean a range of

about 4.4 hours at 5 gph.

Dream on! Most owners plan

on about 3 hours of

flying. But while chasing

birds and shooting down

the enemy, who wants to

fly cross-country anyway.

Simplicity is the word.

The fuel gauges are sight

tubes in the cockpit. The

nosewheel is a castoring

unit, steering is by

differential braking. This

wears out the brakes

sooner but also makes

parking in tight places a

breeze. Backing into the

hangar is an impossibility

without a tow bar (the

American Yankee

Association used to have a

"push your Yankee

backwards" competition

without using a tow bar!).

In general, everything

about the AA1 series is

simple. The ailerons and

flaps are on a long torque

tube. The tail feathers

are interchangeable, as

are the wings. The

maingear legs are

fibreglass. Most Yankees

are simply equipped. One

reason is room, another is

weight, but the best is

KISS - Keep It Simple

Stupid. The airplane was

designed as a trainer

(although many question if

it really was); it wasn't

designed for long

cross-country. Buying and

flying a Yankee is for

sheer enjoyment, not for

corporate transportation.

In 1972, Grumman acquired

American Aviation, and

released the improved

AA-5B with a more powerful

engine. A further upgraded

model, the Tiger,

was also offered.

Improvements to the basic

AA-5 in 1976 led to the

AA-5A and its upgraded

version, the Cheetah.

In 1978, Gulfstream

purchased Grumman

American, and AA-5

production paused whilst

production rights were

sold. It was not until

1990 that American General

Aircraft Corporation

returned the type to

production, as the AG-5B.

American General stopped

trading in 1994. The type

is now again manufactured

by Tiger Aircraft.

What about Safety?

Most pilots know the

airplane as the Yankee but

it went through a few

changes that also changed

the model names. Over 1770

aircraft were built from

1969 to 1978. The original

American AA1 Yankee

Clipper came out in 1969,

and the Yankee model

continued through 1971.

This first model was one

of the fastest; it also

had one of the worst

reputations for handling.

The wing airfoil and the

overall design created a

fast airplane that had a

quick stall (i.e.

dangerous for the

inexperienced) that would

roll over on a wing if the

pilot was behind the

airplane. It also lacked

enough rudder to get out

of spins. Placards noted

that spins were bad. In

fact, NASA did a spin test

with a Yankee and used

ballistic chutes to get it

to stop. Not good!

In 1971, the AA1 became

the AA1A and included a

better airfoil that

provided softer stall

characteristic. The 1973

model was the AA1B, which

offered the choice of

"trainer" with a climb

prop or "sport" with a

cruise prop. But 1977 saw

the biggest changes. The

original 108-hp Lycoming

O-235-C2C engine was

traded for a Lycoming

O-235-L2C that developed

115 hp. These models also

got a 1600-lb gross weight

and a larger elevator. The

T-Cat was the trainer and

the Lynx was the sport

version. (A bit of trivia:

Lycoming says that all

O-235 engines produce 115

hp at 2650 rpm. Is that

neat or what?)

Small and cheap to

operate, the Yankee had

the potential to be

better. Whatever the

negative results of the

design, the aircraft is

fun if flown by

knowledgeable pilots. As a

trainer it's considered

too "hot" by most because

it has a few nasty habits

that usually show up with

inexperienced pilots. Most

instructors prefer

teaching in a Cessna, but

there are some more

experienced instructors

who feel the "demanding

habits" of the Yankee make

it a better trainer,

helping students develop

more high-performance

skills. The Yankee is

definitely not for the

faint of heart or the slow

of reflex!

The aircraft is cute,

usually painted (from the

factory) in bright,

unusual aircraft colours -

red, yellow, orange, even

camouflage - anything to

set the aircraft apart.

The bright colours also

help the aircraft overcome

its small size. It has a

wingspan of 24'. A Cessna

150 has a span of 32'!

With an empty weight of

about 1000 lbs and a gross

of 1500 lbs, the useful is

only about 500 lbs (fuel,

passengers, and stuff). My

stuff usually weighs more

than is supposed to be

carried, especially with

my above-FAA standard 185

lbs and full fuel of 22

gal. Do a few

calculations: 185 lbs

pilot plus 132 lbs for

fuel equals 317 lbs. That

leaves 183 lbs for

passengers and baggage -

not really your

cross-country aircraft.

But if you think about the

aircraft design - small,

quick, fun, fuel thrifty -

it really has more of the

makings of a good

Sunday-morning-breakfast-flight

aircraft anyway. Just

watch the weight.

Compare the AA1A with the

Cessna 150 in the

specifications at the end

of this article. It's

amazing how close they are

in basic performance. They

require about the same

distances, same fuel burn,

etc. The numbers are

pretty close! Maybe the

Yankee isn't as "hot" as

some want you to believe?

Flying Fast

One thing to always

remember about the Yankee,

whatever model, is that it

likes pavement and it

likes runway. I never flew

mine intentionally out of

anything with less than

2000' of hard surface to

run on. That doesn't

include clear space at the

ends. Most insurance

companies want a runway

that has about 1.5 times

the takeoff distance over

a 50' obstacle. That means

at least 2100' of runway

for the AA1 (takeoff over

50 is 1400'). If it's hot,

look for more or stay

home! I said intentionally

because when I was

ferrying my aircraft home

for the first time, I had

to land on a grass strip

for fuel. It was the only

runway pointing into the

wind, a wind strong enough

that I couldn't hold a

slip towards touchdown and

stay over the runway. I

must admit that if it

wasn't for the high winds

and only myself on board

(and the flat, ploughed

fields of the Midwest), I

wouldn't have made it out

of the airport. The flight

in ground effect included

a turn to stay away from

the house on the property!

Taxiing is easy. With a

full-castoring nosewheel

all you do is roll and

touch, kind of like using

a computer mouse. Roll the

direction you want to go

and push the brakes to

turn the aircraft. The

concept is, again, simple.

Plus, when you get into

those tight parking spots

all you do is taxi in,

hold the brake, and the

Yankee turns around!

The long takeoff gives the

feeling of being in a

fighter. Roll down the

runway and at 60

indicated, start lifting

the nose. The nose comes

up but the mains stay on

the ground while the

airspeed builds. At about

65 mph the mains get light

and the aircraft flies

around 70. Keep the plane

in ground effect until 80

mph is reached and you

have a decent climb. Get

too slow and look for the

clearing at the end of the

runway. Patterns are the

same, fast and fun.

Downwind about 90 to 95

and final about 80. The

Yankee has flaps, not much

of flaps, but flaps. Stall

is around 64 mph without

flaps and 60 with flaps;

not a big difference in

speed, but the airplane

does have a solid feel

with the flaps.

Don't get behind the

"power curve." The Yankee

will sink like the

proverbial brick if you

let it. Carry power at all

times. This is good

practice for heavy,

high-performance aircraft

or many of the

Experimental aircraft on

the market. Keep the speed

up and keep the power

on... to keep the Yankee

in the air and make it

flyable. (My Smith

Miniplane does the same

thing, as does a Pitts S1,

Volksplane, and any number

of other aircraft.)

Make sure that landings

are mains first and not on

the nose. The "springy"

nose gear looks neat,

turns neat... and bounces

really high. In fact, it's

so bouncy that if you hit

the nose gear first, you

probably ought to make a

go-around right away. If

you try to save the

landing and start

bouncing, you get into an

oscillation that takes off

the gear and/or hits the

prop - not a nice claim on

your insurance.

|